Sugarcane in Pakistan 2025–26: A Detailed Overview

Syed Hamza Ali

Sugarcane in Pakistan 2025–26: A Detailed Overview

Under the British Raj, the subcontinent’s cane production and sugar refining industry was reorganized into the predecessor of the commercial industry we see today. After 1947, Pakistan inherited the industrial base with only a couple of mills producing a modest amount of refined sugar. From that small beginning, the industry would expand rapidly in the decades that followed. This article will not only talk about the sugar mills in Pakistan but also discuss how the sugar rate in Pakistan is set for farmers and consumers alike.

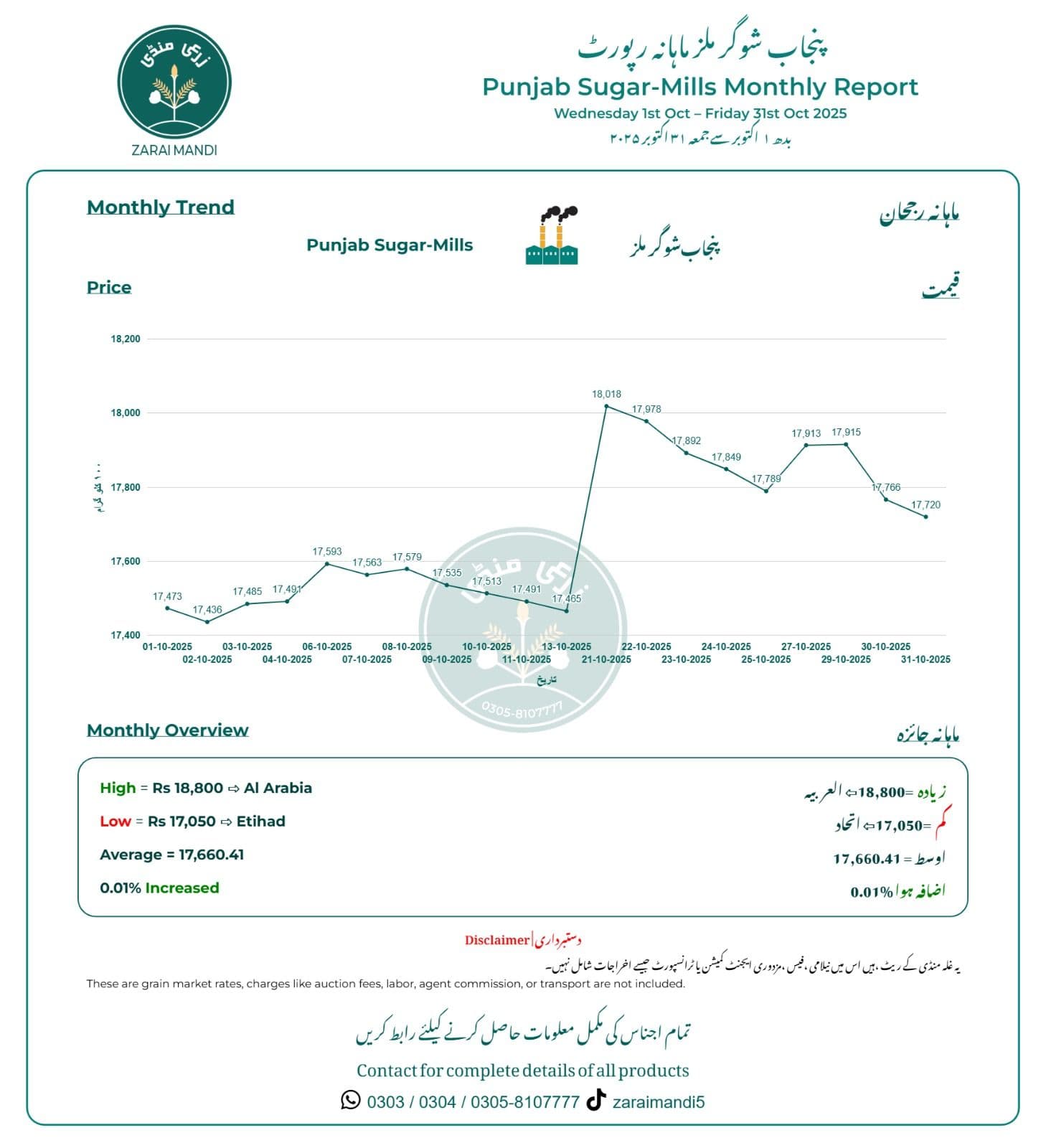

Fig 1: Monthly Sugar Mill Trend

- Figure 1 shows that sugar prices per 100 kg fluctuated between Rs 17,050 (Etihad) and Rs 18,800 (Al Arabia), averaging Rs 17,660.41.

- A sharp spike occurred around 13 October, peaking at Rs 18,018 before gradually stabilizing near Rs 17,720 by month’s end.

- Overall, the report notes only a 0.01% price increase, indicating relative stability in mill rates across Punjab during October 2025.

How is Sugarcane Cultivated in Pakistan?

Sugarcane (known locally as Ganna) is a massive cash crop that is responsible for contributing 1.9% to the national GDP and supports millions of households nationwide. However, its cultivation involves navigating complex agronomic challenges, particularly concerning its long growth cycle, intense water requirements, and the inevitable pressure from competing staple crops like wheat.

Sugar Growth Cycle & Varieties

Sugarcane is classified as a long-duration crop. This means that it demands meticulous planning due to its multi-seasonal growth pattern. The sugarcane cycle in Pakistan, located in the sub-tropics, typically spans 10 to 15 months for spring sowing and ratoon crops, or up to 15 to 18 months for autumn-planted cane.

Sowing generally occurs during the spring (February–March) or autumn (September–October). Autumn sowing is highly preferred as it yields 20–30% higher cane and results in higher sugar recoveries due to a longer growing season. The period from June to August marks the boom period of growth, requiring the highest water input. The crop enters the maturity and ripening phase from October onward, induced by cool, dry weather and declining temperatures. After the initial plant crop is harvested, the stubbles are left to regrow in a practice known as Ratooning. The ratoon crop matures 3–5 weeks earlier than the plant cane and saves substantial production costs (30–35%), offering higher sugar recovery earlier in the crushing season.

Local variety development focuses on selecting varieties for their yield, quality (sucrose content), and resistance to environmental stresses.

- Promising high-yield varieties include CPF-237 and CP77-400, which the Punjab Agriculture Department is actively promoting to replace older strains whose productivity has declined due to prolonged cultivation.

- The variety BL 4 is known for its high yield potential and quick growth habit, though it performs poorly in terms of ratoonability in Punjab.

- Co 1148 is recognized for its high ratoonability, enabling growers to retain the crop cycle longer.

- JDW Mills has produced its own seeds, J16-639 and J16-487, for sugarcane, which is showing a promising future.

Planting Timing & Wheat Rotation Pressure

The timing of sugarcane crushing is a critical economic concern in Pakistan as it directly impacts the farmers’ ability to maximize returns across multiple cropping seasons.

Farmers face intense pressure to clear their fields quickly to accommodate the timely sowing of the subsequent wheat crop. Groups such as the Pakistan Kissan Ittehad often urge the provincial governments to mandate that sugar mills start crushing operations by early November (e.g., November 1). This ensures the land is available for wheat sowing before the crucial window closes. Any delay currently beyond November 20 is considered a threat to the yield of the staple cereal and potentially impacts national food security. Despite this agricultural pressure, crushing typically begins around mid-November. The Federal Minister for National Food Security & Research announced the sugar crushing season would commence from November 15, 2025, a decision made in consultation with provincial authorities and the Pakistan Sugar Mills Association (PSMA). This timing is intended to ensure growers receive a proper return while maintaining a smooth supply of the commodity.

Why Speed Matters: Sucrose Loss After Cutting

As soon as you harvest sugarcane, it starts losing sucrose—so it needs to be transported to the mill as soon as possible. This negatively affects sugarcane production in Pakistan. Sugarcane is highly sensitive to its environment immediately after cutting, and begins a rapid process of deterioration. This deterioration accelerates rapidly under warm weather conditions, making the cane harvested during warmer months (November and March) subject to larger losses than the cane harvested during the cooler winter months of January.

This post-harvest staling affects two major components of value: loss in total weight (due to drying and evaporation) and irreversible loss in sugar recovery (due to biochemical changes in the juice). Stalling also risks exposure to dextran, a gummy colloidal substance produced by microbial infection, which is highly damaging. High dextran levels increase the viscosity of syrups and massecuites, reducing the rate of crystallization and filtration. In severe cases, high dextran levels can reduce a factory’s crushing capacity by 50–70% and increase excessive scale formation on equipment.

How Mills Set Buying Sugar Rates Today?

The purchasing rates and timing for sugarcane (the sugarcane rate in Pakistan) are primarily determined by a blend of government intervention, market competition (or lack thereof), and immediate crop maturity factors. Mills like JDW Sugar Mills, Madina Sugar Mills, Khazana Sugar Mill, and Habib Sugar Mills are leading stakeholders in the sugar supply chain.

The government plays a fundamental role by setting the Minimum Support Price (MSP), such as the Rs 400/ 40 kg set by the Punjab government for the 2023-24 season. This price setting, however, is not always transparent or timely; the support price for the 2024-25 season, for instance, has yet to be announced. In fact, the government is thinking of going for deregulation measures due to IMF pressures and to mitigate the risks associated with the mass production of sugarcane.

Mills operate under a formula where a minimum price is fixed based on a base sugar recovery level (e.g., 8.5% for Punjab). To encourage quality, an incentive (quality premium) is given if the mill's average recovery exceeds this base level. However, this premium is paid to all growers supplying cane, irrespective of the quality of their individual consignment. These mills may also delay crushing if they have sufficient existing sugar stocks. Conversely, they may speculate, purchasing cane based on anticipated future sugar prices in both national and international markets. When the cane supply is short, competition may lead to an unrealistic escalation of the purchase price.

Why is Sugarcane problematic for Pakistan?

For sugarcane cultivation to be successful, robust management of soil fertility, water resources, and pests is required, particularly given Pakistan’s semi-arid climate. As established before, sugarcane is highly water-intensive, and its cultivation is a primary driver of the country's water crisis. And since the Musharraf era, Pakistan has continued with the disastrous policy of sowing sugarcane in water-stressed areas such as South Punjab, destroying the groundwater levels.

Water intensity & groundwater depletion

Water is sourced primarily through canal networks (meeting 50–60% of needs) and groundwater accessed via tubewells. Frequent irrigation is required, especially during the grand growth stage (May-June) when pan evaporation rates are highest, necessitating intervals of 9–11 days in hot months. Pakistan's crop water productivity (CWP) for sugarcane is notably low at 2.28 kg/m³, requiring 53.5% more water than the global average (3.5 kg/m³) to produce the same sugar output. In other words, the crop consumes approximately 3.5 times more water than the competing cotton crop. Despite high yields in weight, the monetary return on water is drastically lower for sugarcane. One litre of water used in cotton production generates about four times higher monetary benefit than sugarcane at the farm gate. When considering the retail level, one litre of water used in cotton production generates about 171 times higher monetary benefits than sugarcane.

Residue Burning & After-Effects

Burning trash residue after cane harvest is a usual practice in Pakistan. This disposal method has immediate and severe environmental repercussions, directly contributing to atmospheric pollution, a known precursor to seasonal smog events.

- Emission of Gases and Pollutants: Burning sugarcane trash leads to substantial material loss, converting organic matter into harmful gases and ash. Specifically, trash burning results in the loss of 90–95% of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur as gases to the atmosphere. Furthermore, smoke pollutes the environment with CO2 gas.

- Loss of Soil Nutrients: Beyond atmospheric harm, burning also releases 80–90% of phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium as air-borne ash, depleting soil fertility. This requires increased input of external fertilizers later.

- Biological Damage: The heat generated in the field destroys beneficial elements such as useful soil microbes, parasites, and predators, thereby upsetting the natural biological balance essential for pest control and soil degradation.

Conclusion

The complex data and political policies surrounding Pakistan's sugarcane industry confirm that the sector operates under intense pressure from public-private interventions, climate volatility, and inherent structural inefficiencies.

Hence, the path toward sustainable sugar production requires phasing out policy-driven market distortions, which currently encourage environmentally detrimental cultivation patterns. Focus must shift toward developing technical efficiencies. Ignoring key economic and ecological trade-offs guarantees continued market instability and accelerates the depletion of critical national water resources.