Pakistan Floods 2025: Crisis, Climate, & Politics

Syed Hamza Ali

Pakistan Floods 2025: Crisis, Climate, & Politics

Pakistan’s 2025 monsoon was neither an anomaly nor a surprise. It was the latest chapter in a long story of climate-charged monsoon variability intersecting with fragile infrastructure, contested water politics, and an agricultural economy that feeds most Pakistanis while employing nearly two in five workers. Understanding what happened—and what must change—requires bringing recent numbers of flood in pakistan into a longer arc: from river basins and urban nallahs to farm sizes and seed systems, and from humanitarian relief to structural reform aimed at food security, resilience, and equity.

A Brief History Of Exposure

Flood risk in Pakistan is historically shaped by the Indus system and its tributaries, seasonal monsoon dynamics, and recurring glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) in the north. The 2022 Pakistan floods impact reset expectations of what “extreme” looks like; 2025 did not match that scale nationwide, but it reproduced familiar vulnerabilities, from breached embankments to submerged cropland and overwhelmed city drains. UN situation reporting this season traces impacts from late June, with a notable Glacier Lake Outburst Flood in Ghizer (Gilgit-Baltistan) on 22 August—an event type that will remain part of Pakistan’s flood risk portfolio as high-mountain cryosphere change accelerates.

What Is Happening Now?

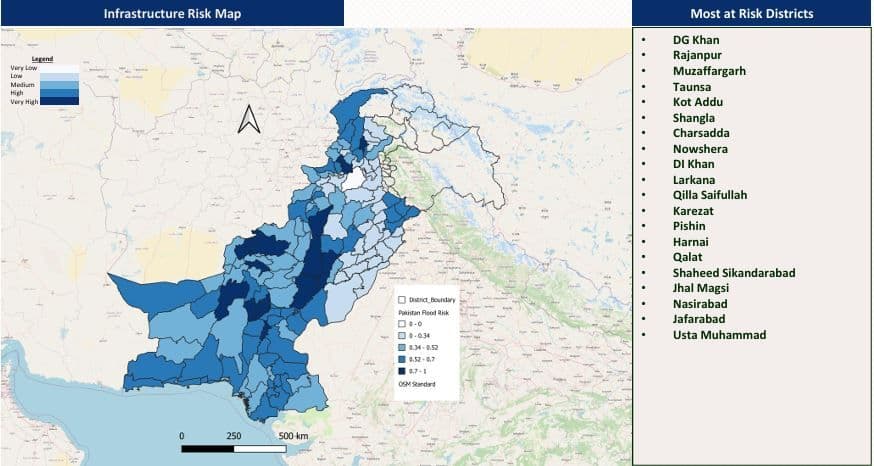

Fig 1.1: Flood affected areas in Pakistan map. Courtesy of NDMA.

Authoritative humanitarian snapshots converge on the same picture on the flood situation in pakistan: a long monsoon window beginning 26 June 2025, punctuated by heavy rainfall bursts and riverine surges that cascaded from Punjab to Sindh while also producing lethal flash floods in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). As of 11–12 September, UN OCHA and UNICEF tallied 932–946 deaths and ~1,060 injuries, with KP carrying a disproportionate share of casualties and damage to health and WASH services; by 2 October, NDMA’s final consolidated situation report aggregated 1,037 deaths and 1,067 injuries since 26 June. These are not just numbers; they signal prolonged exposure, repeated evacuations, and a moving front of water that complicates relief logistics and recovery planning.

Provincial profiles differ. Punjab declared emergencies and mounted mass evacuations as the Ravi, Chenab, and Sutlej overtopped embankments, displacing well over a million people in rolling waves. Sindh agriculture flood damage comprised mostly of elevated flows at Guddu and Sukkur in early-mid September while Karachi wrestled with urban flooding. KP faced flash-flood mortality in mountainous districts and damage to clinics and water systems.

Damage To Crops: Acreage, Timing, And The Rice Signal

The headline figure from Punjab is stark: over 2.2 million acres of crops damaged or submerged by mid-September, with rice the single largest hit (more than a million acres), but significant losses to cotton, sugarcane, and maize. Thankfully, due to the season, Pakistan was saved from flood damage to wheat in Punjab. Independent press coverage and provincial assessments align on both the order of magnitude and the commodity mix. Reuters’ national accounting places agricultural losses alongside broader economic shocks, warning of >10% national crop output losses in some estimates and billions in damages as sowing windows narrow.

Satellite analysis strengthens the crop story. GEOGLAM’s September special report shows a significant reduction in rice area in early September 2025 versus September 2024, precisely when paddy is sensitive to prolonged inundation. Some recovery appears after mid-September as waters recede, but the early-September signal captures foregone yield and quality risks that will echo into prices and milling margins. For a food-security narrative, this is the pivot: flood timing plus crop phenology equals outsized crop loss.

Changing Agricultural Landscapes

Floods do not only wash out a single season; they reshape fields. Repeated inundation leaves waterlogging and salinity scars, disturbs soil structure, deposits sand, and damages minor irrigation, seed stores, and on-farm machinery. Humanitarian reports from Punjab and KP record disruption to nutrition services, input supply, and local markets—factors that depress recovery and affect the Rabi (wheat) cycle now coming due. The agronomic consequence is a patchwork of delayed sowing, reduced seedbed quality, and higher input costs to reclaim fields—costs that smallholders struggle to absorb. The government needs to step in to develop a flood early warning system and assisting mitigation strategies such as flood-adapted sowing calendar to help them escape this devastating cycle.

Response: What Worked And The Need For Scale

Early response hinged on evacuations, medical and nutrition camps, and WASH interventions, and other flood relief strategies particularly in KP and Punjab. UNICEF reports rapid reactivation of outpatient therapeutic nutrition services and emergency water provision; Sindh authorities expanded relief camps and veterinary support while moving livestock—often the shock absorber for rural households—out of harm’s way. Federal and provincial disaster agencies issued frequent advisories, and NDMA closed the monsoon period with consolidated casualty and damage tallies to inform post-flood planning. The immediate lesson is capacity: speed matters, but so does the ability to sustain services as flood waves migrate downstream.

Political Tensions And Accountability

Flood response is never apolitical. Accusations over upstream releases, debates on center–province coordination, and budgetary sparring over relief and reconstruction surfaced again in 2025. The essential governance issue is less rhetorical than practical: how to finance embankment maintenance, drainage rehabilitation, and social protection for smallholders at scale and on time. Reporting this season flags the fiscal risks: a tightening macro outlook, rising import needs (from food to farm inputs), and pressure on growth projections—an uncomfortable trifecta in a year that was supposed to consolidate stabilization and not post-flood recovery.

Are We Out Of The Water?

Meteorological outlooks for Sep–Nov 2025 suggested normal to slightly above-normal rainfall in the east (central-southern Punjab, southeastern Sindh) and nearer-normal or slightly below-normal in the north and west. That pattern helps taper riverine threat as the monsoon withdraws, but it does not resolve saturated soils or damaged infrastructure. For planners, the correct frame is not “over” but “transition”: from acute flood management to pre-Rabi field rehabilitation, seed distribution, and targeted drainage repair before winter cropping windows close.

Rivers Of Karachi: Lyari, Malir, And Urban Flood Mechanics

Karachi’s 2025 floods were driven less by river catchments than by stormwater hydraulics: heavy rain over short windows, Lyari and Malir rivers running high, and a lattice of encroached nullahs and blocked outfalls. Multiple accounts documented deaths, relocations of 300+ people, and inundation of neighborhoods such as Saadi Town/Garden as the two rivers swelled. Subsequent reporting tied persistent inundation to drainage capacity and land-use planning, not just rainfall intensity. That is a governance and engineering problem: enforcement against encroachments, de-silting, designed conveyance to the sea, and stormwater retention—not ad hoc pumping—must anchor the urban agenda.

Stress Zones: Where The Next Failure Looms

This season’s “stress zones” mimic the flood situation Punjab and this is legible in the data: upper-to-mid Punjab for riverine floods and cropland submergence, northern KP for flash-flood mortality and access constraints, and urban Sindh for drainage-driven flooding. OCHA’s flood bulletins flagged high flows at Guddu and Sukkur on 9–10 September; NDMA’s final sitrep counts show Punjab with the highest cumulative fatalities; UNICEF’s sectoral updates underscore WASH and health fragility in KP and parts of Punjab. A district-level composite—population affected, crop share, WASH damage, and access—would put names to risk and help sequence scarce recovery funds.

What Needs To Change: A Policy And Investment Agenda

1) Protect food security by securing the Rabi window. This season’s damage peaked in Kharif rice and cotton; the near-term lever is to prevent cascading losses into Rabi wheat. That means emergency seed and fertilizer support targeted to districts with the worst waterlogging and sand deposition; rapid repair of watercourses; and time-bound cash transfers to smallholders to restore seedbeds. Punjab and federal authorities should align with humanitarian logistics already in motion to consolidate “seed-to-sowing” pipelines.

2) Rebuild with drainage first. The cheapest climate adaptation for much of the irrigated plains is functional drainage. Funds should prioritize desilting and rehabilitation of drains and small canals, with monitoring built into contracts and citizen reporting. Karachi’s case is instructive: without clear conveyance (Lyari/Malir) and protected rights-of-way, any “smart city” promise will drown. Similar logic applies to peri-urban Punjab towns that flooded as backwater effects from major rivers overwhelmed local drains.

3) Upgrade flood forecasting and transparent situation reports. PMD’s seasonal outlooks were directionally sound; what is needed next is district-scale forecast communication fused with NDMA’s sitrep cadence and OCHA’s mapping so farmers, markets, and local administrations can act earlier. Packaging actionable guidance for canal closures, seed timing, and harvest mobilization will save more value per rupee than emergency procurement after the fact.

4) Make recovery pro-poor by design. Given the smallholder dominance documented by the census, public funds should cap support at modest land ceilings; tie cash to simple land/labour identifiers; and route livestock support (feed, vet camps) to restore household balance sheets. Prevent elite capture by publishing beneficiary lists at the union-council level and auditing by random spot checks. Equity is not an add-on—without it, recovery enlarges gaps.

5) Ensure the harvest, not the calamity. Pilot area-yield index insurance for rice and wheat in flood-prone districts using GEOGLAM and NDMA/OCHA exposure data for triggers. Subsidize premiums with catastrophe funds while enforcing anti-fraud through independent crop-cutting or satellite cross-checks. The point is to stabilize smallholder incomes, not socialise agribusiness risk.

6) Align trade and stocks with climate signals. Reuters’ reporting on crop losses and macro spillovers underscores the need for an agile import and reserve policy. Wheat and pulse procurement should anticipate price spikes from damaged Kharif and set thresholds for timed releases to protect poor consumers without crushing farmers’ recovery prices.

7) Finance resilient infrastructure with accountability. Whether through concessional climate finance or domestic re-prioritization, the next rupee should go to assets that cut flood losses: embankment maintenance, siphons and regulators, all-weather rural roads for evacuation and market access. A public dashboard that ties contractors, work completion, and pre-/post-monsoon inspections to maps can convert political scrutiny into public value.

Conclusion: From Crisis To Capability

The 2025 floods do not demand a new theory of Pakistan. They demand a new practice. The data already tell us where the water goes, who gets hurt, and which crops fail when inundation comes at the wrong week. The Indus will continue to carry monsoon excess; Lyari and Malir will continue to drain Karachi; small farms will continue to absorb the shocks first. The only durable answer is to lower exposure (drainage and land-use enforcement), raise adaptive capacity (seed systems, forecasting, insurance), and target support where the census says most farmers live: on small plots where a single failed season becomes debt. If policy centers these realities—food security, resilience, and fairness—then the next monsoon will test a more capable state and a more protected rural economy, not the same brittle system we watched again this year.